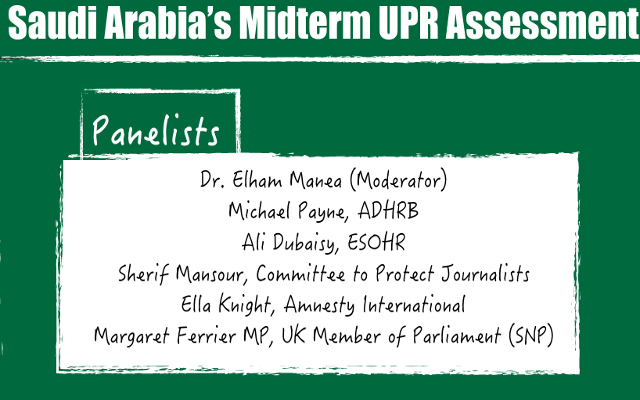

16 June 2016 – Geneva, Switzerland – Today, Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain, alongside the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, and a large group of partner NGOs held a side event marking Saudi Arabia’s 2nd cycle Universal Periodic Review (UPR). The panel event was moderated by Dr. Elham Manea from the University of Zurich. The event marked the publication of ADHRB’s new Midterm Report on Saudi Arabia’s UPR Second Cycle.

16 June 2016 – Geneva, Switzerland – Today, Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain, alongside the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy, and a large group of partner NGOs held a side event marking Saudi Arabia’s 2nd cycle Universal Periodic Review (UPR). The panel event was moderated by Dr. Elham Manea from the University of Zurich. The event marked the publication of ADHRB’s new Midterm Report on Saudi Arabia’s UPR Second Cycle.

Dr. Manea introduced the event by highlighting Saudi Arabia’s mid-term UPR. She explained that Saudi Arabia had accepted 187 UPR recommendations from a total of 225. Despite this, the human rights situation has deteriorated.

Michael Payne, ADHRB’s International Advocacy Officer, highlighted how Saudi Arabia has attempted to pursue a larger role in international arena. Saudi Arabia is currently a member of the Human Rights Council now and in 2015 considered campaigning for President of the Council. The power gained by Saudi Arabia has been used to drastically cover up human rights abuses and silence other states from criticizing them. ADHRB’s report has found only one fully implemented recommendation out of a total of 225. 113 have not been implemented, 64 technically implemented with no impact, and 9 partially implemented. In the thirteen thematic areas into which the government grouped its 187 accepted recommendations, ADHRB found measurable progress for only five. Civil society has lost its protections after newly amended laws and a new law on association was introduced to target minority groups and religious leaders. Mr. Payne called on the international community to urge the kingdom to implement in full its UPR recommendations. Before becoming leader on the world stage, it must respect human rights at home.

Ella Knight from Amnesty International spoke about how states welcomed Saudi Arabia when it originally accepted 187 UPR recommendations. When these were examined closely, however, important contradictions gave an indication of the level of engagement that Saudi Arabia had actually taken with the UPR. Vague promises were made to make some changes, rather than concrete pledges to implement them. This was reflected later on. An example was given when Saudi Arabia accepted recommendations to “consider ratifying ICCPR” however rejected recommendations to outright ratify it. Ella raised serious concerns over the lack of seriousness and unwillingness of Saudi Arabia to address the violations that it has continued to commit throughout its membership in the Human Rights Council (HRC). Accepting UPR recommendations was argued to be merely a public relations exercise intended to deflect international criticism. Important concerns were raised in regards to the lack of reforms to the judicial and law enforcement systems. Systemic use of anti-terror laws to prosecute peaceful human rights defenders is a central concern in Saudi Arabia. In response to UPR recommendations in this area, Saudi Arabia claimed that it guaranteed freedom of expression, while Amnesty continues to document the repression of all forms of dissent. All rights defenders in Saudi Arabia are either in prison, intimidated into silence, or exiled.

New counter-terror laws introduced by the kingdom equate terrorism and peaceful free expression. The legislation prevents contact with international bodies and censors the press. Waleed Abu Khair, a human rights lawyer, was the first person to be sentenced under this new law over two years ago. He was charged with “disobeying the ruler” and “harming the reputation of the state.” Waleed refused to recognize legitimacy of Specialized Criminal Court (SCC) during the trial and is now serving 15 years in prison. Saudi Arabia has also taken the extreme step to shut down the civil society organisation ACPRA, arresting and imprisoning all of its members including Abdulaziz al-Shubaily and Isa al-Hamid. Both were charged with “communicating with foreign organisations” such as Amnesty International.

Although Saudi Arabia has accepted recommendations for judicial and legal system reform, it has not even taken basic steps to implement them. The kingdom accepted a recommendation to ensure all individuals are afforded transparent trials however the Saudi justice system still lacks basic protections for due process. Confessions obtained under duress or torture are regularly submitted as evidence to convict defendants.

Although Saudi Arabia has accepted recommendations for judicial and legal system reform, it has not even taken basic steps to implement them. The kingdom accepted a recommendation to ensure all individuals are afforded transparent trials however the Saudi justice system still lacks basic protections for due process. Confessions obtained under duress or torture are regularly submitted as evidence to convict defendants.

Ella concluding by arguing that the quantity of recommendations accepted by the kingdom is immaterial without clear steps taken to implement them on the ground. There has been a Saudi attempt to whitewash its human rights record and to make the international community think that they are reforming. In order to prevent scrutiny and accountability, it is using its diplomatic clout at the HRC to defend itself. For example it has used its position on the HRC to block an international investigation into the war in Yemen and to remove itself from the UN child abuse list. The HRC must take steps to hold Saudi Arabia accountable for its systemic human rights violations.

Ali Adubisi from the European Saudi Organisation for Human Rights (ESOHR) spoke about the Saudi government’s mentality on the UPR, and how it was able to understand and predict the outcome of the review. He also noted that in the last five sessions of the HRC, he has not seen any other Saudi activists apart from himself. The repression in Saudi Arabia has resulted in this lack of civil society representation and it allows the kingdom to continue to abuse civilians and whitewash its poor human rights record. It has moreover created fake NGOs and used them to support its stances in abusing human rights. For example, Saudi Arabia made claims that it had consulted with civil society concerning the UPR, such as the National Society for Human Rights (NSHR). However, after the mass executions in the kingdom earlier this year, the NSHR issued a statement supporting them.

Independent activists continue to be targeted. From the beginning of the second UPR cycle until today, the Saudi government has dissolved ACPRA and sentenced all 11 cofounders to prison, including al-Shuabaily, who recently received a sentence of eight years in prison. Accepting the UPR recommendations without a civil society precludes the possibility for actual reform. For the last two years, the government has made almost no effort, and therefore achieved no real practical outcomes. The fact that it accepted recommendations should not be used as a guarantee to trust Saudi Arabia at all. There is a big difference between what the kingdom says and what it does.

The death penalty continues to be used against minors and children. This is because Saudi laws are in contradiction with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Prosecuting minors is actually on the rise, and most of these cases relate to peaceful protests. As a result, Saudi Arabia lacks credibility in its statements at the HRC defending its rights record. Just weeks before its most recent speech, for example, an individual was tortured to death in policy custody.

Ali also spoke about his experiences as a victim of torture in 2011, and argued that the UPR may not be the best way to tackle the most urgent rights abuses in the kingdom, such as imminent executions. The HRC needs to establish a mechanism for urgent action rather than solely relying on the UPR. Since the second UPR cycle, the number of executions in Saudi Arabia has escalated to at least 350.

Sherif Mansour from the Committee to Protect Journalist began by commending Saudi activists, saying it was extremely rare for any Saudi to speak about what they think in the current climate. Last week’s successful Saudi move to censor the UN and force it to remove its name from child abuse blacklist is one of the most unfortunate and disappointing news in a long time. Activists will begin to think that it is futile to even engage with the UN after the move. It should be a wake-up call for all member states and all delegates if the UN cannot even exercise its right to document. This also reflects how limited civil society is in Saudi Arabia, and how civil society actors are unable to speak up.There is no way to discuss rights in Saudi Arabia because the government silences and intimidates anyone who does.

CPJ analysis from its world censorship report places Saudi Arabia as the third worst censor of the media in the world. The situation has deteriorated and Saudi Arabia has become a closed media environment. Since the Arab Spring in 2011, this environment deteriorated even further. Saudi Arabia is also the eight worst jailer of journalists worldwide, with several behind bars today. This censorship has been going on for decades. In 2011, the Ministry of Culture was given authority to review all online content and resulted in the expansion of restrictions.

In August 2015, after Wikileaks published documents from the Saudi Ministry of Foreign Affairs, it was made clear how the kingdom used its influence and money to buy media organisations and journalists in order to lobby regional and international agencies and to silence criticism. There has been a new batch of regulations to make online media the same as traditional media to prevent independent journalism leading to censorship. The Commission for Audiovisual Media has targeted YouTube videos critical of Saudi Arabia and the government, and have cracked down on all videos discussing Saudi issues.

Raif Badawi is one of the most important cases illustrating censorship and reprisals. His health is in danger after going on hunger strike and states must act to secure his release. Saudi Arabia has also criminalised reporting on protests in Shia minority areas. In the case of Husain al-Salam, the government accused him of “inciting sedition and threatening public order” for merely reporting on protests