The Office of the Ombudsman for Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior (MOI) released its fifth annual report on 4 October 2018, further whitewashing both rampant police misconduct and its own role in perpetuating the cycle of abuse. Covering the period from 1 May 2017 to 30 April 2018, the report presents the work of the Ombudsman’s Office to fulfill its mandate to “do justice” by investigating cases of police and other MOI malfeasance in line with the principles of “independence, credibility, impartiality, accountability and transparency.” During the period under review, however, the Ombudsman’s Office has violated all of the purported core values “underpinning [its] work,” ultimately failing to hold almost any security personnel responsible for widespread gross human rights abuses. Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) condemns the Ombudsman’s misleading report and remains deeply concerned by the institution’s consistent refusal or inability to adequately and independently monitor the MOI police force.

The MOI is Bahrain’s chief internal security force, and it systematically violates human rights to suppress dissent. It is responsible for the vast majority of everyday abuses that occur in the kingdom, with ADHRB alone documenting hundreds of incidents of gross misconduct perpetrated by the MOI consisting of thousands of individual human rights violations. The ministry comprises some of the kingdom’s most brutal security institutions, including the Criminal Investigations Directorate (CID), Bahrain’s main torture hub; the Special Security Force Command (SSFC), which includes militarized anti-terror and riot police; the Cybercrime Directorate, which enforces unlawful social media offenses against journalists and human rights defenders; and the notorious prison system, run by the General Directorate of Reformation and Rehabilitation (GDRR). After the MOI led the violent crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in 2011, the Ombudsman’s Office was established in accordance with recommendations of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI) to combat the culture of impunity for police crimes. Nevertheless, the institution was structurally flawed from the start, and it has had no discernible impact on the rates of severe human rights violations perpetrated by the MOI as a matter of policy.

The MOI is Bahrain’s chief internal security force, and it systematically violates human rights to suppress dissent. It is responsible for the vast majority of everyday abuses that occur in the kingdom, with ADHRB alone documenting hundreds of incidents of gross misconduct perpetrated by the MOI consisting of thousands of individual human rights violations. The ministry comprises some of the kingdom’s most brutal security institutions, including the Criminal Investigations Directorate (CID), Bahrain’s main torture hub; the Special Security Force Command (SSFC), which includes militarized anti-terror and riot police; the Cybercrime Directorate, which enforces unlawful social media offenses against journalists and human rights defenders; and the notorious prison system, run by the General Directorate of Reformation and Rehabilitation (GDRR). After the MOI led the violent crackdown on pro-democracy protesters in 2011, the Ombudsman’s Office was established in accordance with recommendations of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI) to combat the culture of impunity for police crimes. Nevertheless, the institution was structurally flawed from the start, and it has had no discernible impact on the rates of severe human rights violations perpetrated by the MOI as a matter of policy.

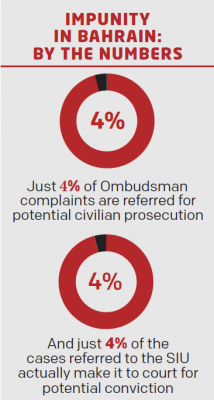

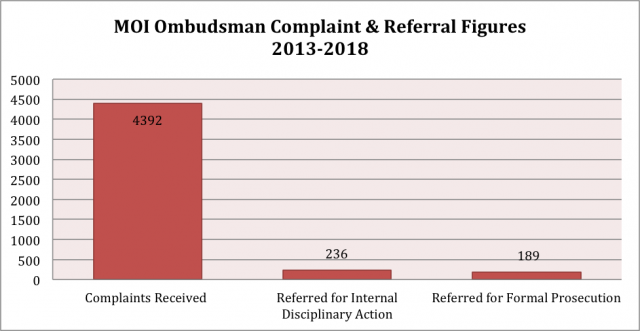

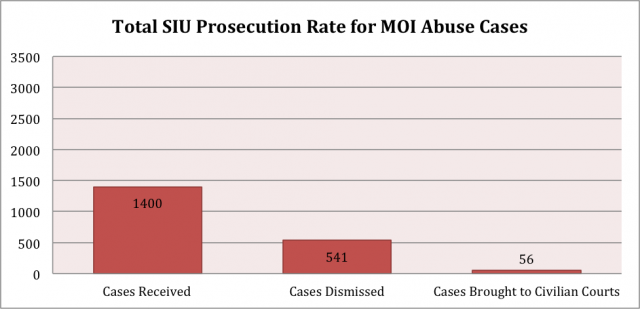

The statistics provided in the 2017/2018 report demonstrate the continued failure of the Ombudsman Office to address Bahrain’s culture of impunity for official misconduct. According to the Ombudsman, the institution received a total of 1,094 complaints and requests for assistance over the past year – a decline of roughly 30 percent from the previous reporting period, when the Ombudsman received a total of 1,156. The vast majority of cases were submitted by individuals, with 50 from international organizations and three from local organizations. Just one case was launched by the Ombudsman of its own initiative, underscoring the institution’s continued reluctance to take a more active role in investigating police abuse. Of the 1094 total cases, only 120 were “referred to relevant bodies” for potential disciplinary action; of these, just 30 were referred to the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) of the Public Prosecution at the Ministry of Justice and Islamic Affairs (MOJ), the entity responsible for actually bringing cases of police abuse to court. The remaining 90 cases were transferred to the MOI’s internal disciplinary branch – known as the Security Court system – which has reportedly been barred from handling incidents of severe abuse like “torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or deaths linked thereto” since 2012 over concerns of partiality and opacity. As such, these figures reveal that the Ombudsman’s Office pursued serious accountability measures for gross rights violations in a mere three percent of cases raised over the last year. Moreover, since its establishment, the SIU has only referred 4 percent of the total cases it has ever received to civilian criminal courts, meaning that even of the 30 cases transmitted by the Ombudsman’s Office for 2017/2018, only one will likely make it to trial. These are abysmally low accountability rates purposefully obscured by bureaucratic complexity.

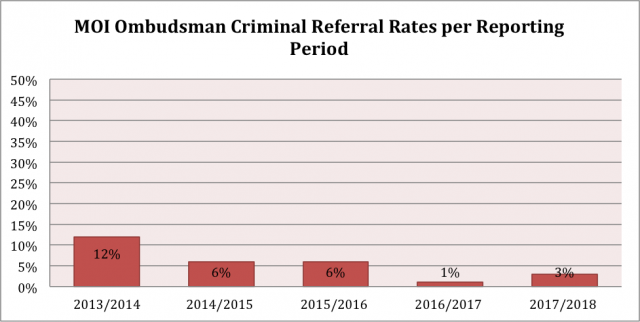

Although the proportion of criminal referrals for 2017/2018 is slightly higher than that of 2016/2017 – likely reflecting the disparity in the number of complaints received – the Ombudsman’s overall criminal referral rates have largely decreased since the institution was founded. The rate of referrals to the Public Prosecution Office (PPO) or SIU dropped from 12 percent in 2013/2014 to 6 percent in both 2014/2015 and 2015/2016, down to just one percent in 2016/2017. With this year’s rate of three percent, it brings the average annual rate of referral to less than six percent. Of the 4,392 total complaints and requests for assistance received by the Ombudsman from 2013 to now, this year’s rate lowers the ultimate proportion of cases transferred for potential serious accountability from five percent to four. Coupled with the equally low SIU prosecution rates, this means that effectively only four percent of four percent of complaints – or less than one percent – actually make it to court, let alone result in conviction.

Notably, to mark its first five years of operation, the Ombudsman’s Office included extended descriptions of three past cases that it saw as “illustrative” of its best practices, including the torture and conviction of Mohamed Ramadan and Husain Moosa; and the March 2015 collective punishment of Jau Prison inmates. However, while these are certainly instances of severe police abuse, the Ombudsman’s Office largely covered up or failed to adequately address these violations – both at the time, and in the fifth annual report’s retrospective.

For example, in the case of Mohamed Ramadan and his codefendant Husain Moosa, the Ombudsman Office itself was identified by a group of UN experts as conducting “flawed and insufficient” investigations into the allegations of torture, with the experts expressing their concern at the “absence or at least serious delay of a thorough, independent and impartial investigation or prosecution into the allegations of torture and ill-treatment” and particularly “concern at the entrusting of this important investigation to the same State institution, the Ombudsman’s Office, whose earlier investigations raised serious doubts regarding their independence, professionalism and thoroughness.” The Ombudsman, while touting this purported “success” story, does not address these serious allegations of wrongdoing from the UN. Further, while the report explicitly celebrates the Ombudsman’s role in advancing the case of Ramadan and Moosa for reconsideration by the Court of Cassation in light of evidence of torture, it makes no indication that the Ombudsman is actively investigating the perpetrators of such torture.

Likewise, the report glosses over the allegations of mass torture that followed the MOI’s violent suppression of unrest in Jau Prison in March 2015, which itself stemmed from overcrowding and inhumane living conditions within the facility – a problem similarly omitted from the report. MOI personnel used excessive force to regain control of the prison, firing tear gas into enclosed spaces and beating inmates indiscriminately, including minors. The authorities continued to torture the inmates after quelling the protests, beating them and depriving them of food and sleep. Some inmates were specifically targeted and forcibly disappeared elsewhere in the prison. The authorities took many political prisoners and those suspected of instigating the unrest to Building 10, which imprisoned human rights defender Abdulhadi al-Khawaja has described as “the torture building.” At least 100 inmates were transferred to Building 10 in the weeks following the riot. Police who hesitated to abuse the prisoners were reprimanded and transferred. While the government claims to have installed some cameras in Jau, much of this abuse occurred in the lobbies, bathrooms, or solitary confinement cells where there is no official surveillance. On 15 April 2015, the United Nations (UN) human rights experts issued a joint communication to the Government of Bahrain in which they noted that the violent assault resulted in the injury of approximately 500 inmates – nearly 400 more than the Ombudsman’s excessively low estimate of 104. The UN experts also expressed concern that the authorities had rearrested human rights defender Nabeel Rajab after he documented cases of torture in Jau; Rajab is now imprisoned there for that same offense, despite a decision from the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention declaring his incarceration unlawful.

The Ombudsman’s report ignores or downplays all of these abuses, highlighting only that 13 MOI personnel were ultimately referred to the courts on assault charges in January 2018 – more than two full years after a court convicted 57 prisoners on charges stemming from the same incident in January 2016. Ten of the 13 officials were sentenced to just six months in prison on minor charges – not torture – while the 57 inmates received additional 15-year prison terms. The disparity in both length of investigation and severity of penalty highlights the separate and unequal judicial treatment of security personnel in Bahrain, aided and abetted by the Ombudsman.

Beyond these cases, the report ultimately disregards other major trends and incidents of MOI police abuse throughout the reporting period. For example, while the Ombudsman claims it has “investigated every death in detention in Bahrain,” it has entirely failed to address numerous extrajudicial killings implicating the MOI outside of centers of detention. The report makes no mention of the 23 May 2017 police raid on a peaceful protest in Diraz, for example, which left five demonstrators dead and hundreds injured. It was Bahrain’s bloodiest day in years, and UN experts explicitly condemned the MOI’s conduct “as neither necessary or proportionate and therefore excessive, qualifying the five deaths as unlawful killings.” The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights called on the “Government to investigate the events of 23 May, in particular the loss of lives, to ensure that the findings are made public and that those responsible are held accountable” – a request that the Ombudsman wholly refused to meet.

As with its previous report, the Ombudsman also indicates that the government has continuously failed to fully implement several key reform recommendations of the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI), which were thereby reiterated by the Ombudsman. Though it attempts to praise the MOI for having “increased significantly” the installation and use of CCTV cameras, this again contradicts the MOI’s claims in 2014 and 2015 to have officially placed cameras in all detention centers and prisons. As recently as 2016, other government reports[1] clearly stated that the MOI’s immigration detention centers were not covered by CCTV surveillance. Even in facilities that have installed cameras, the systems never cover all of the possible interrogation areas, and ADHRB has consistently documented personnel simply taking detainees into bathrooms or other unmonitored locations within the prison system before torturing them. Inmates report that there are no cameras monitoring Jau Prison’s solitary confinement cells, for example, and in 2017 ADHRB documented cases where guards turned out the power to cell blocks before raiding them and conducting random beatings.

Finally, the Ombudsman’s Office explicitly misrepresents the extent of international support for the institution: in the conclusion of his foreword, Ombudsman Nawaf Mohammed al-Moawdah highlights the European Union (EU)’s 2014 decision to jointly bestow the Chaillot Prize for the Promotion of Human Rights in the Gulf Cooperation Council Region on the Ombudsman’s Office and Bahrain’s National Institution for Human Rights (NIHR), an equally flawed semi-independent oversight body. Yet, just this year, in June 2018 the European Parliament issued a resolution criticizing Bahrain’s accountability mechanisms for failing to fulfill their mandates to combat impunity, stating that it explicitly “regrets” that the “EU Delegation’s Chaillot prize … was awarded in 2014” to Bahrain’s institutions.

Throughout the period covered by the Ombudsman’s fifth annual report, ADHRB has even recorded evidence of the Office directly engaging in the human rights violations its meant to investigate, including by assigning personnel accused of wrongdoing to process complaints; abusing its authority to interrogate complainants and their families; endorsing abusive policies; and otherwise exposing complainants to reprisal by MOI personnel, including the Ombudsman’s own staff. Most recently, the Ombudsman’s Office actively participated in Bahraini government efforts to obfuscate the mistreatment of prominent political prisoner Hassan Mushaima after his son, Ali, launched a high-profile hunger strike in protest of inhumane restrictions imposed on his father.

Ultimately, the Ombudsman’s Office’s fifth annual report is misleading and incomplete, and a careful analysis of the institution’s own statistics confirms its complete inability or unwillingness to combat impunity for police brutality in Bahrain. The office is dangerously ineffective and there is increasing evidence that it is directly complicit in human rights abuses. Its failures further demonstrate that Bahrain’s labyrinthine arrangement of internal and pseudo-independent oversight bodies, each with complex and varied authorities, is at its base intended not to secure accountability for perpetrators, but to further obscure near-absolute immunity for security personnel. ADHRB echoes the recent findings of the UN Committee Against Torture, among other expert bodies, which expressed serious concern over the Ombudsman’s independence, impartiality, and efficacy. We condemn the Ombudsman’s deepening role in the MOI’s broader campaign to suppress basic human rights, and we call on the Government of Bahrain to urgently take new good faith measures to hold perpetrators responsible for their abuses.

[1] Report 11 – Unannounced Visit to the Men’s Removal Center (MRC), PDRC, MOI, Kingdom of Bahrain, 2017, http://www.pdrc.bh/mcms-store/pdf/0ad15b6e-6cc8-4ab1-8573-a9dd3619ef80_Mens%20Removal%20Center-English.pdf; and Report 12 – Unannounced visit to the Women’s Removal Center (WRC), PDRC, MOI, Kingdom of Bahrain, 2017, http://www.pdrc.bh/mcms-store/pdf/6c5fdde8-3403-420e-a561-3822e6d0dbb4_Women%E2%80%99s%20Removal%20Center-English.pdf