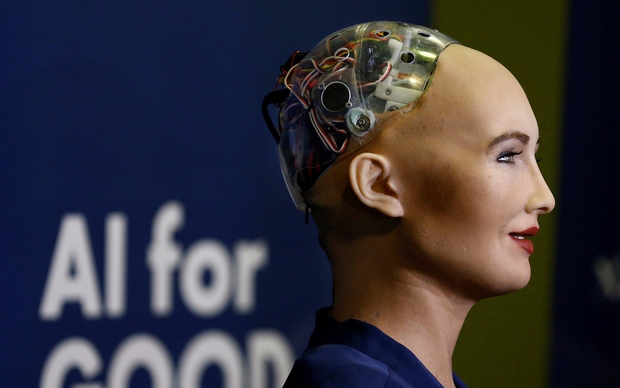

In late October, Saudi Arabia granted a robot, called Sophia, citizenship, making it the first robot in the world to officially become the citizen of a state. However, the decision to grant Sophia the privileges of a Saudi national has engendered sharp criticism concerning the kingdom’s treatment of women, in particular the continued imposition of the restrictive male guardianship system and the resulting lack of equality and fundamental freedoms between genders.

The announcement about Sophia’s citizenship came during the Future Investment Initiative summit in Riyadh on a panel entitled “Thinking Machines: Summit on Artificial Intelligence and Robots.” The Initiative was a business forum aimed at exploring investment opportunities in Saudi Arabia and promoting the kingdom as business-forward and investment-friendly. Thus the announcement of Sophia’s citizenship during the Initiative was a way for the kingdom to position itself on the forefront of technology business. However, the move has drawn scrutiny and criticism because of Saudi Arabia’s stance on women’s rights. Women in Saudi Arabia enjoy neither legal nor practical equality due to the kingdom’s system of male guardianship, whereby every woman must have a guardian empowered to make important decisions on her behalf. Because of the restrictions of the guardianship system, Saudi women are largely rendered legal minors.

However, in gaining citizenship, Sophia has obtained a number of rights and privileges not available to many women and girls, as well as other Saudi residents. Among the strictures of the guardianship system is a hierarchy of personal status between women and men that grants only men full citizenship rights and prevents women from passing citizenship to their children. Thus, Sophia has citizenship when many children born to Saudi mothers but non-Saudi fathers do not. Hadeel Sheikh, a Saudi woman with a four-year-old child that lacks citizenship because the father is a foreign national, told Reuters: “It hit a sore spot that a robot has citizenship and my daughter doesn’t.” Furthermore, Sophia has citizenship when the thousands of migrant workers who have lived in Saudi Arabia for years, and whose labor has built much of the country’s infrastructure, do not.

The details of her appearance at the Initiative have also been cause for comment. Where women have been arrested and faced death threats for dressing “immodestly,” including without an hijab or abaya, Sophia appeared in public with neither. Sophia also appeared in public without a male guardian, something women are restricted from doing. In addition, there have been somewhat facetious questions about whether Sophia can leave Saudi Arabia without a guardian’s consent, as women are not allowed to leave the country unless their guardian acquiesces.

While Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is reversing some longstanding policies concerning women in Saudi Arabia, foremost among them the ability to drive and attend some events in sports stadiums, the lack of gender equality is still a serious problem. The guardianship system remains in place, with gender mixing in public largely banned and women still required to obtain their guardian’s approval in order to get married or travel outside the kingdom. More fundamentally, women are not treated the same as men and they must still receive approval from their male guardian before they engage in certain tasks and actions.

The decision to grant Sophia Saudi citizenship has drawn attention to Saudi Arabia’s ongoing problems of systematic gender inequality and reminded many of the restrictions forced on women by the male guardianship system. While the kingdom is seeing some reforms at a rapid rate, the fundamental structure of gender inequality remains untouched: women must have a male guardian who can make important decisions for them without their consent. Saudi Arabia must work to end the male guardianship system and ensure that women have equality under the law.