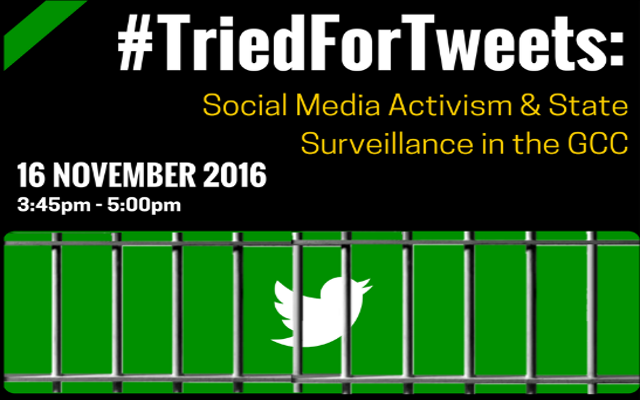

16 November 2016 – Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) held an event at American University in Washington, DC, on how state surveillance by Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) governments has negatively affected human rights activists and other civil society members’ social media use. ADHRB’s Advocacy Fellow, Mobashra Tazamal, hosted the event. Panelists included: Adrian Shahbaz, Research Manager at Freedom House; Ahmed Mansour, award-winning Emirati human rights defender; Margaux Ewen, Advocacy and Communications Officer at Reporters Without Borders (RSF); and Marc Owen Jones, PhD, research fellow at Exeter University in the United Kingdom.

Mobashra Tazamal began the event by giving an overview on the situation of GCC state surveillance and how that has severely restricted freedom of expression in the GCC. In Bahrain, for example, human rights defender Nabeel Rajab has been convicted for his social media use and charged with 15 years in prison. Courts continue to postpone his trial; his next hearing is on 15 December, when they could sentence him. Tazamal noted Rajab is not the only individual in the GCC to be imprisoned for expressing his opinion online. ADHRB has documented a number of cases where governments violated individuals’ rights to freedom of expression. Other activists and individuals who have been targeted by the Bahraini government include Taiba Ismail, Ghada Jamsheer, Fadhel Abbas and Faisal Hayyat. Additionally, Human Rights Watch (HRW) published a report with profiles of 140 prominent Bahraini, Kuwaiti, Omani, Qatari, Saudi, and Emirati social and political rights activists and dissidents. The report highlights the sharing of the worst practices by GCC states as each of the six countries are guilty of violating free expression. These individuals include Waleed Abu al-Khair and Mohammed Fahad al-Qahtani from Saudi Arabia, Ahmed Mansour and Mohammed al-Roken from the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Rana al-Sadoun and Ayyad al-Harbi from Kuwait, Mukhtar al-Henai and Muawiyah al-Rawahi of Oman.

Adrian Shahbaz first highlighted the recent release of Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net 2016 report, which considers the following GCC countries “not free:” Bahrain, with a score of 71/100; the UAE, with a score of 68/100; and Saudi Arabia, with a score of 72/100. Human rights organizations, bloggers who question religion or criticize the royal family, journalists who work on investigative reports on torture, and independent news sources are all subjected to censorship and criminal charges. Shahbaz noted that once one GCC country implements new measures to further censor media, other GCC states may likely follow. For example, Bahraini authorities have charged Twitter users for speaking out against the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, which has cause a massive humanitarian crisis. Additionally, all of the GCC countries have employed broad anti-terrorism laws to curb free speech. Anti-terrorism laws in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain have made non-violent peaceful dissent a crime which can result in years in prison. Although the Bahraini constitution technically guarantees freedom of speech and press, a network of legislation – primarily the penal code, the press law, the anti-terror law, and the cybercrime law – empower the authorities to prosecute individuals on a range of offenses related solely to journalism or expression. In the UAE, the case of academic Dr. Nasser Bin Ghaith, illustrates the Emirati authorities’ efforts to restrict free expression.

Ahmed Mansour next presented his own case as a target of UAE surveillance and harassment. Recently, Mansour was a victim of a hacking attempt. Citizen Lab, an organization in Canada, discovered the hacking technology, bought by the Emirati government from an Israeli organization costing one million dolalrs. As soon Citizen Lab discovered the spyware, they contacted Apple. In response, Apple updated its software and alerted its customers. The hacking technology, if activated, jailbroke Mansour’s iPhone 6 remotely and installed sophisticated software. Citizen Lab writes “once infected, Mansour’s phone would have become a digital spy in his pocket, capable of employing his iPhone’s camera and microphone to snoop on activity in the vicinity of the device, recording his WhatsApp and Viber calls, logging messages sent in mobile chat apps, and tracking his movements.” Mansour also spoke about how money was withdrawn from his bank account and his car was stolen after a prosecution hearing; he believes this could be the work of Emirati officials. He recalled a time when the United Nations Special Rapporteur was present with him on a visit to discuss the situation of human rights in the UAE, and their car was followed by unidentified agents. Due to the UAE government’s extensive surveillance of Mansour, he no longer uses phone calls to communicate and uses other social media at great risk.

Margaux Ewen of RSF focused her remarks on GCC states’ specific targeting of journalists and bloggers for their social media use. Press freedom in the GCC countries is among the worst in the world. Anti-terror laws and cybercrime laws heavily censor social media outlets, though this contravenes Article 19 of the UN International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Bahrain and Kuwait are both state parties to the ICCPR. The Government of Bahrain has recently charged Faisal Hayyat for “defamatory” tweets, and he could be could face prison for his social media use. Hayyat is a former sports journalist and social media activist who is involved in an online video program that provides a critical perspective on local politics in Bahrain. Ewen noted that Hayyat’s case could be compared to a hypothetical scenario in the US where Jon Stewart were charged for his video program, which is critical of American politics. Ewen additionally presented Raif Bedawi’s case. The internet is the only space where free information can circulate, but it is heavily monitored. Publishing comments that are in any way critical of the Saudi government comes at the risk of criminal charges and imprisonment. In Bedawi’s case, Saudi courts sentenced him to 1,000 lashes, a travel ban, and 10 years in prison. Judges convicted Bedawi under the Saudi anit-cyber crime law for allegedly insulting a religion in comments he made on his website and on television. RSF finds that the Government of Bahrain has imprisoned eight professional journalists and five citizen journalists. RSF finds that the Government of Saudi Arabia has imprisoned eight professional journalists and two citizen journalists.

Marc Owen Jones was the last panelist to speak. He noted that in 2011, the social media “world” in Bahrain was very different from what it is today. During the pro-democracy movement, there was a sense of hope and people used Facebook and Twitter to take photos of themselves during protests. Jones says photos like this do not appear as commonly anymore. The government targeted some protestors after they appeared in pictures protesting. Since the increasingly-harsh repression in Bahrain over the summer of 2016, Jones has discovered a recent twitter bot phenomenon. These twitter bots are posting sectarian comments and including commonly-used hashtags. Jones notes this is meant to clog up the hashtag feed in order to bury legitimate tweets, many of which comment on the arbitrary revocation of citizenship of Sheikh Isa Qassim and the peaceful sit-in around his house in Diraz. These propagandistic tweets artificially skew the news from the region to give a pro-government view about the recent measures taken by Bahriani authorities. The Bahraini government often uses sectarianism as a tool to divide the population. Jones is a member of Bahrain Watch, a NGO that recently uncovered technical evidence that forces deliberately disrupted mobile phone services in Diraz to prevent communication among the protesters.