Background

Kuwait gained independence in 1961, ceasing to be a British protectorate anymore. Upon this development, one-third of the population was given nationality on the basis of being ‘founding fathers’ while another third were naturalized as citizens. The remaining people were designated as bidoon jinsiya which when translated from Arabic means ‘without nationality’. According to Minority Rights Group International, this group of people, mostly from tribal rural areas did not register for citizenship due to either unawareness of the new law’s importance, illiteracy, or a failure to provide adequate documentation. This bidoon label would cause considerable consequences for their descendants for decades to come, and these challenges are still present today. At first, the Bidoon population was not treated vastly differently from citizens. They had access to education, medical services, and employment. The only major freedom they were deprived of was the right to vote.

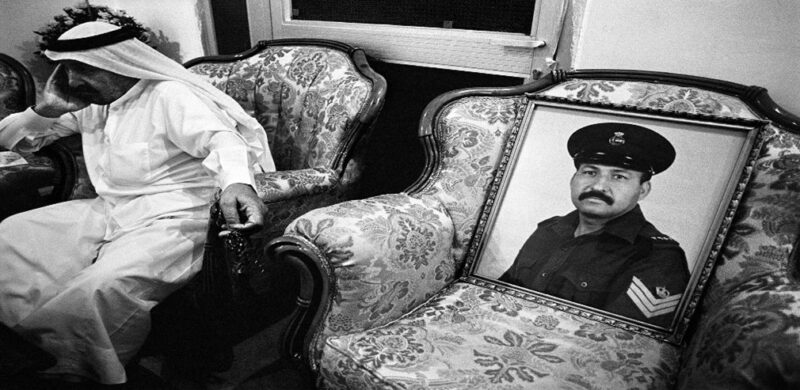

This all changed in 1986 when the government declared them ‘illegal residents’, and their rights were slowly taken away from them. The Kuwaiti government insisted that they were nationals of another state despite an appeals court ruling the opposite in 1988. Then the Gulf War happened and as the Bidoon made up the majority of the Kuwaiti army, they were blamed for any advancement of Iraqi forces. After the war, some soldiers were tried in military courts for collaboration with Iraq, Bidoon refugees were not allowed to return to their homes and around 10,000 were reportedly deported. The Bidoon population dropped from 250,000 to 100,000, and those that remained faced many new issues. They were denied identification documents and constantly harassed to reveal their ‘true nationality.’

These challenges followed the Bidoon people into the 21st century and by 2011, the community was rightly frustrated. On February 18th, 2011, the first protest took place. This was during the time of the infamous Arab Spring so the government not wanting any trouble, promised minor changes to quell the protests. However, by March 10th there had been no promises fulfilled so protests broke out again. This time, the government responded with extreme force. Over 140 people were detained without charge despite reports that the protests were completely peaceful. The government responded again with promises that basic rights would be given to the Bidoon people. Ten years later and the community is still waiting. This can be seen in the fact that on the 27th of April of this year, NPR reported that six Bidoon men were sitting outside a police station for the previous 19 days on hunger strike, demanding their rights. Eleven years on and the Bidoon community still has a very simple demand for the Kuwaiti government – their basic rights. So, let us look at the challenges these people are facing today.

Modern Challenges

Amnesty International estimates the current population of Bidoon in Kuwait is approximately 100,000. Recently, the US Department of State released their country reports on Human Rights Practices for the year 2021. The Bidoon population are mentioned throughout the Kuwait report, highlighting the many deprivations of basic rights they face daily. Firstly, the Bidoon people are prohibited from demonstrating and peacefully assembling due to their non-citizen status. Ironically, the precise thing they are demanding in these protests. There have been reports of harassment by authorities when Bidoon attempted to organize peacefully, and organizers have been detained for even planning events. This violates their right to freedom of assembly. The Bidoon population is mentioned in the political prisoners and detainees’ section again for being arrested and sentenced for organizing public demonstrations. Criticizing the Amir and his policies against the Bidoon on social media can also carry a hefty prison sentence, ranging from six months to ten years. The case of Abdullah Fayrouz was highlighted as he served eight years for insulting the Amir. He was sentenced to exile, but no other country would take him.

It was found that while being detained, the Bidoon people particularly face mistreatment by authorities. These allegations amount to arbitrary detention as well as physical and verbal abuse in custody. The report did find there were some disciplinary procedures for the police involved in cases and there was an effort made in holding these officers to account. The right to freedom of movement was also continuously violated by the Kuwaiti government. Many faced issues traveling due to their lack of travel documents and no official passports. One high-profile case was documented in which a Bidoon child desperately needed medical treatment abroad and was denied. Only after negative media attention did the family get the document they needed. These documents are Article 17 passports that allow travel but do not grant nationality.

In terms of access to education, a basic human right, the path is fraught with difficulties once again for Bidoon children and their parents. Due to their lack of nationality, they are not permitted to attend public schools. This leaves parents with no choice but to send their kids to private schools and be forced to pay the fees. Charitable foundations cover some of the tuition but the quality of education is less than in public schools, according to Minority Rights Group International. Until 2013, Bidoon were not allowed to attend the national university and even now, there is a maximum quota of one hundred students per year and they must excel to achieve a place. This discrimination continues into the workplace where the Bidoon’s illegal status creates even more problems. Government ministries do offer work to Bidoon but on contracts that provide little to no security and do not offer appropriate benefits that citizens are entitled to such as paid sick leave. In one instance, the Ministry of Defense requested that six hundred of its employees renewed their security cards. This is the identification card given to the Bidoon people intended to give them access to basic services. Though, that is not always the case in practice. Once these Defense Ministry workers tried to renew these cards, they were told they must declare a different nationality to get them. It was reported that a man tried to set himself on fire when his request was refused. These are just some examples of the tribulations faced by stateless persons.

In this US State Department report, under the stateless person section, the extreme injustice in the path of gaining citizenship faced by the Bidoon people is detailed. Kuwait does not make it easy for a stateless person to gain citizenship as is shown in the law. Sebastian Kohn, a writer for a piece on the topic in the Justice Initiative interviewed people in Kuwait and found that some believe this lack of will to give the Bidoon people citizenship is because Kuwaiti politics is elitist and people in good social positions have little thought or sympathy for those lesser than them. The judiciary has no power to bestow citizenship. Even citizen mothers do not have the right to pass down their own citizenship to their child if the child’s father is Bidoon. This leaves the child born stateless and perpetuates an endless cycle no matter who the Bidoon people marry and is an extreme form of injustice and inequality for women.

Central System for the Remedy of the Situation of Illegal Residents

The Central System for the Remedy of the Situation of Illegal Residents is the government agency in charge of Bidoon affairs. Just recently, the term of the organization was extended two years beyond its mandate. Amnesty International’s Deputy Regional Director for the Middle East and North Africa, Lynn Maalouf said of the situation “It is deeply disappointing that the Kuwaiti authorities saw fit to extend the mandate of the Central System for the Remedy of the Situation of Illegal Residents – rather than address the pressing need for justice, accountability and the reform of the agency”. There were many protests regarding the decision. The US report found that there have been numerous suicides in the community partially due to failings of this agency to adequately address grievances. One of these suicides was a young 12-year-old Bidoon boy. Since 2010, the system has received tens of thousands of requests for citizenship but data on its approval and denial rates could not be accessed. The report also found that the Ministry of Interior had summoned nineteen activists over the past year for insulting the agency and its activities. The system was assigned the task of fixing the Bidoon problem in 2010 but since its instigation, life for the Bidoon community has severely deteriorated.

International law

Former UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Non-Citizens, David Weissbrodt wrote on the situation in 2008, “at the very least, a person should be eligible for the citizenship of the country with which she or he has the closest link or connection”. Many Bidon has evidence of their historic linkage to Kuwait but Kuwait’s laws on nationality are becoming increasingly strict. This can be seen in the 1980 amendment that prevents women from passing down their citizenship which was discussed earlier. While international law allows states to decide whom can be entitled to citizenship, it is limited in the case that a person may become stateless when denied citizenship. It violates Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which states that “everyone has the right to a nationality” as well as that “no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality.” Kuwait is violating several international treaties to which they are party. Kuwait acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) in 1996 and their treatment of Bidoon violates Article 24 in which the state must protect children from statelessness. In 1991, Kuwait ratified the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child which affirms the right of a child to have a nationality and that “the child shall be registered immediately after birth”. It puts the responsibility on the state once again and Kuwait is failing this responsibility to the Bidoon children of their nation. There are two international conventions on statelessness- UN Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons (1954) and The Convention on Reduction of Statelessness (1961) but Kuwait has not ratified either of these which is very telling of their attitude towards statelessness and their responsibility as a nation-state.

The future for the Bidoon people

While the Bidoon community faces bleak circumstances, they are continuing to fight and demand their rights. As seen by the men conducting a hunger strike only last month, the Bidoon are not accepting their statelessness quietly as Kuwait so desperately wants. The priority for the Bidoon remains naturalization. The international community has called on Kuwait several times over the years to amend its laws and allow the Bidoon to gain citizenship. In 2017, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) called on Kuwait to ensure that the Bidoon had adequate access to social services and demanded they amend their nationality application process. In 2013, Amnesty International called for Kuwait to establish an independent tribunal to access all citizenship claims. Many Bidoon have supported this idea as a path for the future, but Kuwait cited that this process would not be possible due to state sovereignty. Minority Rights Group International in their piece on Bidoon called for at the very least for Kuwait to allow women to pass their citizenship onto their children. They also point out that while these nationality claims are being assessed by the various bodies, that Kuwait takes measures to ensure that the living standards and basic rights of the Bidoon people are met.

Despite these repeated calls for Kuwait to protect its stateless population and repeated promises for change from the Kuwaiti government, the situation remains unchanged. 100,000 people left without a nation to officially call home despite Kuwait being the only home that these people have ever known. They are trapped and treated as aliens in their homeland. A UK exhibition called Nowhere People quoted a member of the Bidoon community as putting it succinctly “Citizenship means for the Bidoon that the whole world acknowledges I am a human being. I have rights. I am human being. Not so much for rights are material. But the right to exist. I exist. I exist as a human.” These people still have hope, and these people are still fighting for their basic human rights and the international community must support them in this mission.