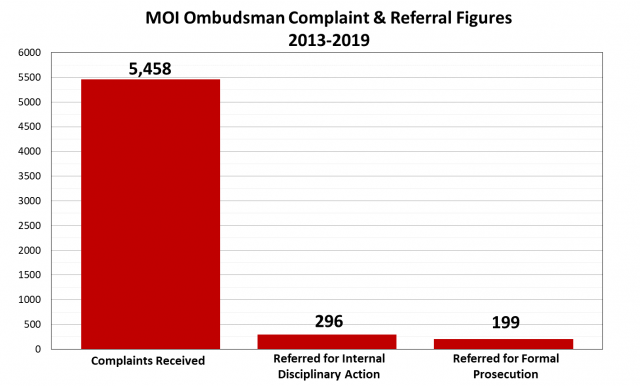

7 October 2019 – On 3 October 2019, Bahrain’s Ministry of Interior (MOI) Ombudsman released its sixth annual report, demonstrating a continued inability to hold perpetrators of abuse accountable. The report covers the period from May 2018 to April 2019, tracking complaints received and actions taken by the Ombudsman to investigate and address these complaints. As in previous years, complaints are rarely referred to relevant bodies, and even less are referred for formal prosecution. This emboldens members of the MOI to continue perpetrating abuses, adding to the culture of impunity in the kingdom. Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) stresses that Bahrain’s MOI Ombudsman is not independent and is unable to uphold its mandate, and further condemns the annual report as a way of whitewashing the Ombudsman’s failures.

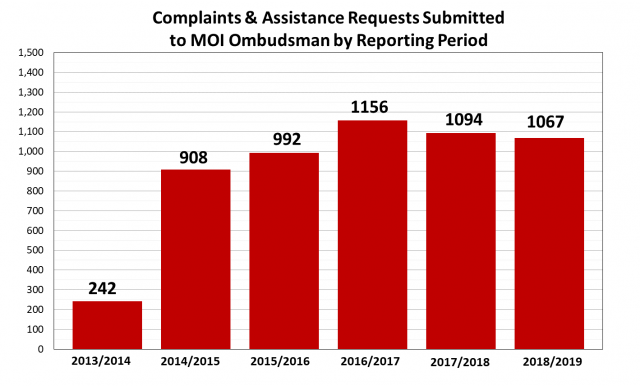

The statistics provided in the 2018/2019 report demonstrate the continued failure of the Ombudsman Office to address Bahrain’s culture of impunity for official misconduct. According to the Ombudsman, the institution received a total of 1,067 complaints and requests for assistance during the reporting period, a slight decline from the 1,094 received in the 2017/2018 period and the 1,156 from 2016/2017. This decrease is likely not the result of fewer abuses taking place, but instead caused fear of reprisal if a complaint is brought before the Ombudsman and a lack of trust in the ability of the institution to have a positive impact.

The statistics provided in the 2018/2019 report demonstrate the continued failure of the Ombudsman Office to address Bahrain’s culture of impunity for official misconduct. According to the Ombudsman, the institution received a total of 1,067 complaints and requests for assistance during the reporting period, a slight decline from the 1,094 received in the 2017/2018 period and the 1,156 from 2016/2017. This decrease is likely not the result of fewer abuses taking place, but instead caused fear of reprisal if a complaint is brought before the Ombudsman and a lack of trust in the ability of the institution to have a positive impact.

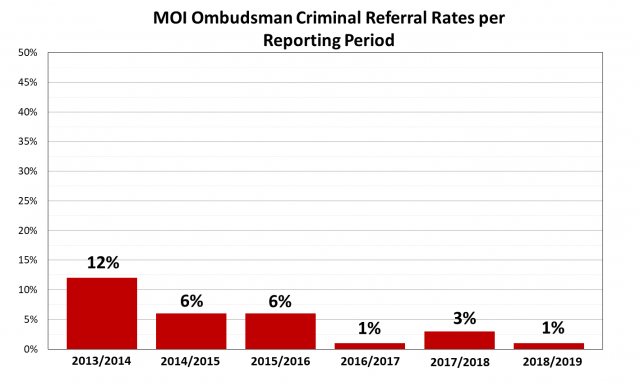

The vast majority of cases were submitted by individuals in the 2018/2019 reporting period, with 78 from international organizations and seven from local organizations. No cases were launched by the Ombudsman of its own initiative, underscoring the institution’s continued reluctance to take a more active role in investigating police abuse. Of the 1,067 total cases, only 70 were “referred to relevant bodies” for potential disciplinary action; of these, just nine were referred to the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) of the Public Prosecution at the Ministry of Justice and Islamic Affairs (MOJ), the entity responsible for actually bringing cases of police abuse to court, and only one case was referred to the Public Prosecution Office. The remaining 60 cases were transferred to the MOI’s internal disciplinary branch – known as the Security Court system – which has reportedly been barred from handling incidents of severe abuse like “torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or deaths linked thereto” since 2012, over concerns of partiality and opacity. As such, these figures reveal that the Ombudsman’s Office pursued serious accountability measures for gross rights violations in a mere one percent of cases raised over the last year, dropping from last period’s three percent. Moreover, since its establishment, the SIU has only referred four percent of the total cases it has ever received to civilian criminal courts, meaning that even of the nine cases transmitted by the Ombudsman’s Office for 2018/2019, it is unlikely that any will make it to trial.

The vast majority of cases were submitted by individuals in the 2018/2019 reporting period, with 78 from international organizations and seven from local organizations. No cases were launched by the Ombudsman of its own initiative, underscoring the institution’s continued reluctance to take a more active role in investigating police abuse. Of the 1,067 total cases, only 70 were “referred to relevant bodies” for potential disciplinary action; of these, just nine were referred to the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) of the Public Prosecution at the Ministry of Justice and Islamic Affairs (MOJ), the entity responsible for actually bringing cases of police abuse to court, and only one case was referred to the Public Prosecution Office. The remaining 60 cases were transferred to the MOI’s internal disciplinary branch – known as the Security Court system – which has reportedly been barred from handling incidents of severe abuse like “torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or deaths linked thereto” since 2012, over concerns of partiality and opacity. As such, these figures reveal that the Ombudsman’s Office pursued serious accountability measures for gross rights violations in a mere one percent of cases raised over the last year, dropping from last period’s three percent. Moreover, since its establishment, the SIU has only referred four percent of the total cases it has ever received to civilian criminal courts, meaning that even of the nine cases transmitted by the Ombudsman’s Office for 2018/2019, it is unlikely that any will make it to trial.

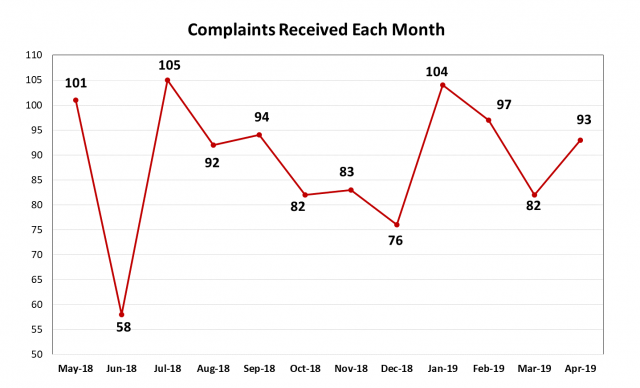

The Ombudsman’s report neglects to provide any analysis or trends of abuses, nor specific events occurring during the reporting period. The high number of complaints submitted in July 2018, which almost doubled from the 58 submitted the previous month, can likely be attributed to the water cuts that occurred at Jau Prison during that time. Water cuts began to Jau Prison on 9 July 2018, concerning multiple buildings, including Building 17, which houses New Dry Dock, the section of the prison dedicated to convicted individuals who are under 21 years of age. It was reported that some water cuts lasted for 36 hours. Victims noted that these cuts impacted both drinking water as well as water for bathing and toilet facilities, contributing to unhygienic conditions and the spread of disease and skin conditions. The water cuts continued through August, despite the fact that Bahrain was experiencing high temperatures of 32-39 degrees Celsius, with a heat index of 38-45 degrees Celsius. Prisoners also reported that they were only given one cup of water to drink per day, and that water was running to the buildings for only one hour per day.

The Ombudsman’s report neglects to provide any analysis or trends of abuses, nor specific events occurring during the reporting period. The high number of complaints submitted in July 2018, which almost doubled from the 58 submitted the previous month, can likely be attributed to the water cuts that occurred at Jau Prison during that time. Water cuts began to Jau Prison on 9 July 2018, concerning multiple buildings, including Building 17, which houses New Dry Dock, the section of the prison dedicated to convicted individuals who are under 21 years of age. It was reported that some water cuts lasted for 36 hours. Victims noted that these cuts impacted both drinking water as well as water for bathing and toilet facilities, contributing to unhygienic conditions and the spread of disease and skin conditions. The water cuts continued through August, despite the fact that Bahrain was experiencing high temperatures of 32-39 degrees Celsius, with a heat index of 38-45 degrees Celsius. Prisoners also reported that they were only given one cup of water to drink per day, and that water was running to the buildings for only one hour per day.

Additionally, some complaints in September 2018 may be attributed to the increased crackdown in Bahrain surrounding Ashura, when 94 complaints were submitted. Ashura processions were disrupted by riot police in 21 villages and several individuals were arrested in connection to participations in Ashura commemorations. Detainees were also discriminated against and punished for attempting to participate in Ashura commemorations, including political prisoner Hajer Mansoor, who was denied the ability to leave her cell with her cell-mates by prison authorities to participate in religious activities in prison and was later allegedly beaten by guards.

Additionally, during the reporting period, the MOI Ombudsman twice breached confidentiality in regard to Hajer’s case, despite supposedly guaranteeing to complainants “[f]ull confidentiality … during the investigations and, according to the law, no-one can access or reveal details about them in any way.” In August 2018, the Ombudsman included the First Secretary of the Bahrain Embassy in London, Fahad Al Binali, as well as the Minister of Foreign Affairs in communications on Hajer’s case without prior consent from Hajer’s son-in-law – who submitted complaints on her behalf. Then in March 2019, the Bahraini Embassy in London published a string of now-deleted public tweets including the correspondence between Hajer’s son-in-law and the Ombudsman regarding allegations of ill-treatment against Hajer, disclosing the email addresses of all those copied in the correspondence, in a gross miscarriage of confidentiality.

Several complaints received during the reporting period of the sixth annual report have been inadequately addressed by the MOI Ombudsman, including for 71-year-old political prisoner Hassan Mushaima – serving a life sentence in Jau Prison for his role in the 2011 protest movement. Mushaima had raised concerns about denial of access to medical care and family visits, as well as having books and reading materials confiscated. In response, the Ombudsman publicly stated it was Hassan Mushaima who refused to go to appointments or visits because of the prison’s policy of needing to be shackled – a practice deemed degrading by Human Rights Watch. While arrangements were made for him to attend some medical appointments without handcuffs, this did not apply to all necessary appointments and shackling policies surrounding family visits remained unchanged. Furthermore, the Ombudsman concluded that Mushaima only was entitled to having two books in his cell at a time, though he previously had many books in his cell.

The Ombudsman also ignored concerns over the conditions of detention for father and son Hani and Hussain Marhoon. Hani Marhoon sent multiple complaints and communications since August 2018, but received no response. These complaints concerned systematic torture and violations of domestic and international human rights laws inside Jau Prison, such as extreme overcrowding and lack of beds. In addition to the complaints submitted during the recent reporting period, Hani Marhoon and his family have sent requests and complaints to the Ombudsman’s office consistently since September 2017, concerning his unjustified solitary confinement, torture, beatings, and other abuses. While the Marhoons eventually received a response from the Ombudsman after ADHRB published a letter concerning their cases, the Ombudsman essentially dismissed all allegations, and their circumstances have not improved.

The failure of these institutions to respond to requests in a timely and appropriate manner amplify the overall concerns about the Ombudsman’s independence. These concerns have been echoed by the international community. In the United Nations Committee Against Torture’s review of Bahrain in 2017, the Committee criticized the Ombudsman, particularly noting its concerns that “these bodies are not independent, that their mandates are unclear and overlapping and that they are not effective given that complaints ultimately pass through the Ministry of the Interior.”

Most recently, the Ombudsman remained completely silent ahead of the executions of torture victims Ali AlArab and Ahmed AlMalali in July 2019, who were both convicted in an unfair mass trial. The office has also not publicly commented on their executions. The office has additionally made public statements on the hunger strikes in Jau Prison protesting poor conditions and Abduljalil AlSingace that parrot the government’s position and dismiss allegations of wrongdoing.

Ultimately, the Ombudsman Office’s sixth annual report lacks any substance, and an analysis of the institution’s own statistics confirms its inability or unwillingness to combat impunity for police brutality and officer misconduct in Bahrain. The office is dangerously ineffective and there is increasing evidence that it is directly complicit in human rights abuses and enables Bahrain’s culture of impunity. ADHRB condemns the Ombudsman’s lack of independence and inability to uphold its mandate, and we call on the Government of Bahrain to urgently take new good faith measures to hold perpetrators responsible for their abuses.