“A distinctive characteristic of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states; Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates: is the prevalence of the rentier economy.” (Bahgat, 1995)

Ever since the discovery of vast reserves of natural resource wealth in the Gulf, the spotlight of the world has shifted towards the East, where new power structures quickly emerged. Wealthy ruling families cashed in on the discovery of oil and gas, and began a long term goal of capital projects aimed at improving the standard of living and strengthening the security apparatus of each state in an increasingly unstable region of the world. However, the division of wealth, or lack thereof, soon became the dominant factor in these countries, with significant swathes of state revenue going toward funding the lavish lifestyles of the region’s monarchs. Concurrent to this was the fruition of systematic corrupt business practices on the part of ruling families, which only served to exacerbate the inequitable governing strategies of the Gulf countries.

In each of the GCC countries, a majority share of government revenue is derived from foreign rents from natural resource extraction, meaning these countries are heavily reliant on these revenues to fund short and long term projects.

“Living like a king”

The exuberant lifestyles enjoyed by Bahrain’s ruling family has become a generic attribute of Gulf royalty across the board. Comparing and contrasting the wealth enjoyed by a privileged fraction of the population to the remaining majority highlights the unjust and unsustainable nature of authoritarian kings and their families.

According to estimates, between 1926 and 1970 Bahrain’s ruling family received about a quarter of the nation’s wealth. The combined amount of money they received together as a family always represented “the largest item of recurrent expenditure.”

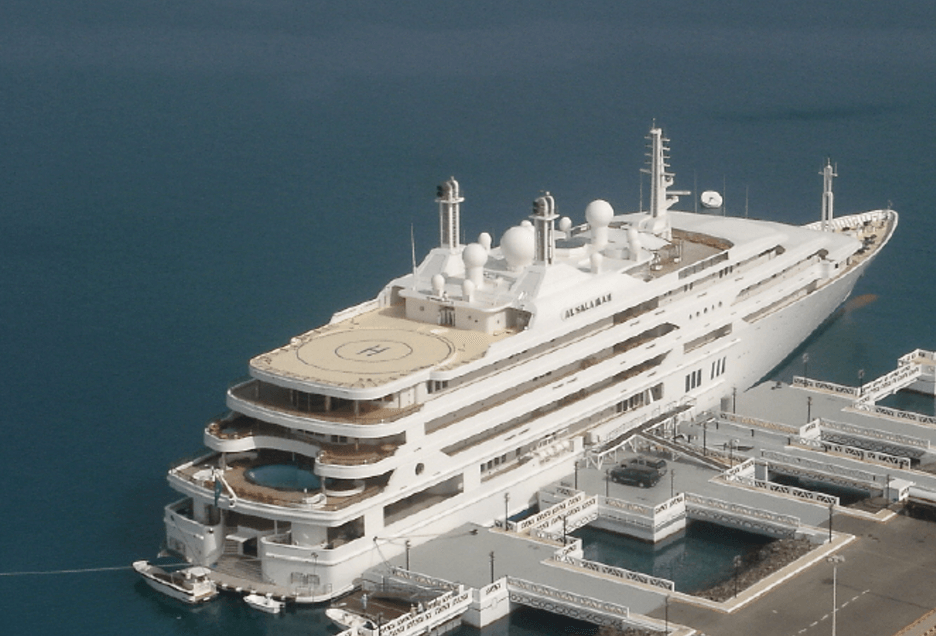

The AlKhalifa family owns a collection of multi-million dollar luxury goods, including the yacht “Al Salamab,” one of the world’s largest by volume. Once on the market for an asking price of $314 million, it was handed as a gift to the Crown Prince of Bahrain by Saudi Arabia. Additionally, the family’s aircraft fleet consists of six aircraft, a Boeing Business Jet BBJ2, two Boeing 747-400s, a Boeing 767-400ER, a Gulfstream G-IV private jet, and a Bell 430 helicopter. The Boeing 767-400ER alone is valued at $250 million.

In 2018, the Guardian reported that Sheikh Hamad Isa Ali AlKhalifa, a cousin of Bahrain’s king and nephew of the country’s deputy prime minister, had been accused of reneging on a promise to pay $35 million to meet 26 Bollywood stars for whom he had an “unbridled desire and fantasy.” The sheikh denied the allegations, and insisted he only expected to be “charged “$30,000 to $50,000 for private meetings” according to the report.

Division of Wealth

Measuring the division of wealth and individual economic return in Bahrain is an invaluable indicator of the many layers of corruption that plague the small island nation. The flow of money between government, businesses, and everyday Bahraini men and women demands transparency and accountability.

It is estimated that 12.2% of Bahrainis live on less than $5 per day, with that number being attributed mainly to Bahraini women, Shia, and foreign workers. The wealth disparity in Bahrain is indicative of the extent of economic corruption between the ruling AlKhalifa family and the people they supposedly govern. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the richest 20% of the population owns 41.6% of the total income earned, reflecting the persisting social inequality in Bahrain.

While the Kingdom of Bahrain ranks particularly well on the Human Development Index, their position is not representative of a significant portion of the population, and is used as a cover to the economic hardship experienced by Bahrain’s majority Shia community. The economic underrepresentation is mirrored in the broader lack of political and judicial representation of the Shia population. A majority of official positions in the Council of Ministers, the Shura Council, and the Council of Representatives, and all of Bahrain’s judges, are appointed by King Hamad, who exhibits a strict bias towards Sunni Muslims within the governing structures of the state. As of 2013, members of the AlKhalifa dynasty held 14 out of 35 Cabinet-level positions, while Shia individuals held only six. The king also maintains the exclusive right to appoint judges and judicial officers. As a result, Shia individuals accounted for just 12% of the judiciary in 2013.

Large imports of weapons and ammunition for Bahrain’s extensive security sector are made at the expense of social housing and economic development, and those same munitions are also routinely used to repress dissent among the politically marginalized Shia majority population. The lack of transparency and accountability over the security sector, as well as its role in the Bahraini government’s broader repression, allows the kingdom to largely resist both internal and external calls for democratic reforms. With a growing level of societal discontent with the Bahraini monarchy, and an inequitable division of wealth to accompany it, the continuation of large domestic defense expenditures without a clear security strategy further delegitimizes the regime.

The exception; routine royal corruption

According to Transparency International, Bahrain scores 36/100 in terms of public sector corruption, 0 indicating highly corrupt, and 100 meaning very clean. As the case studies below will highlight, there seems to be no existing state apparatus that regulates the procurement of government contracts, as well as responsible spending practices by government officials in Bahrain.

In 2014, Alcoa Inc. (an American aluminum company) was charged with bribery by the United States (US) Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) due to their dealings with smelteries in Bahrain. The investigation had found that Alcoa Inc. was bribing Bahraini officials, including members of the royal family, with roughly $110 million over the course of years and that this extensive corruption occurred because Bahrain houses one of the largest aluminum smelters in the world, and Alcoa Inc. would send their raw materials there for refinement, exposing the company to the high levels of corruption found in Bahrain’s private sector.

In an attempt to create the appearance of accountability and transparency when it comes to corruption, the National Audit Court (NAC) was established in 2002 by the King. The NAC was mandated with cracking down on corruption in Bahrain and increasing Bahrain’s dismal standing in the World Corruption Index. However, the ruling elite quickly stripped the NAC of its enforcement competencies, ultimately making it powerless in its fight against corruption. The Alcoa Inc. scandal was never mentioned in any of its reports, further undermining its effectiveness and ability to act independently of Bahrain’s ruling cadres.

In 2014, the Financial Times reported that $40 billion worth of Bahraini public land had been given to private investors without any return payment to the state. Through extensive land reclamation projects, multi-billion dollar real estate developments sprung up around Bahrain’s coastline. The report notes that since 2003, 65km² of public land was transferred to private ventures, worth an estimated $40 billion, or the equivalent of twice of Bahrain’s GDP. However no payments were made to Bahrain’s Treasury. This expensive real estate endeavor was also done at the expense of affordable housing.

Another example is the Bahrain Bay project. This $2.5 billion development that juts out on to what previously was an expanse of water is, according to activists, “a symbol of inequality in a country marred by human rights violations and sectarian strife, where an acute housing shortage persists even as exclusive developments multiply.” The financing of land reclamation projects is done through the public purse, but the public never sees the returns on capital investments. The Premier Group, an investment company reportedly owned by King Hamad, has an estimated investment value of $22 billion, including assets in Bahrain as well as in the United Kingdom (UK). The intricate process of capital accumulation, borrowing, and investing by the Premier Group is all conducted behind closed doors. The use of public funds to finance the commercial ambitions of the ruling family is highly irresponsible and undemocratic, as the reward for such investments returns only to the royals and not the average Bahraini.

“The way this land was acquired has focused questions on the contested line between public and royal land ownership.” (FT, 2014)

Despite the goals of Bahrain’s 2011 pro-democracy movement, hopes of a transition towards an accountable constitutional monarchy has been marked instead by persistent corruption and an inherent willingness to withhold information from the public. How the AlKhalifa family intends to juggle its vast business portfolio and its false claims of accountability and transparency will inevitably dictate how sustainable their economic strategy is in the long run.