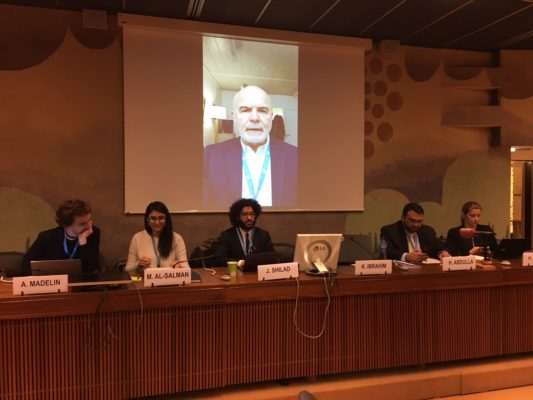

On Tuesday 13 March, Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB) participated in a joint side event organized by the Gulf Center for Human Rights and CIVICUS. Cosponsoring the event are the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, Human Rights Watch, the International Service for Human Rights, Committee to Protect Journalists, Federation of International Human Rights Leagues (FIDH), OMCT, PEN International, and Reporters without Borders. The panel was moderated by Husain Abdulla, ADHRB’s Executive Director, and featured Khalid Ibrahim, the Executive Director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights, Hanan Salah, the Bahrain researcher at Human Rights Watch, Justin Shilad, the MENA research associate with the Committee to Protect Journalists, Antoine Madelin, FIDH’s director of international advocacy, a short video message from Michel Forst, the special rapporteur on human rights defenders, and remarks by Sheikh Maytham al-Salman, a Bahrain interfaith activist.

Husain Abdulla, ADHRB’s Executive Director opened the panel by giving some context to the panel, noting how the Government of Bahrain used its judicial system against human rights defenders and activists. This judicial system has levied harsh sentences against activists, including death sentences against 14 people in 2017 alone, denoting a dramatic spike in capital punishment sentences. Then in January 2017, on top of the death sentences, the government ended its de facto moratorium on the death penalty, executing three torture victims. In addition to the death sentences, Bahrain’s court system has increasingly utilized arbitrary citizenship revocations against activists. Also in 2017, the Bahraini government initiated its first trials against civilians in military courts since 2011, when the government established the National Safety Courts (NSCs), which were used to try peaceful protesters. During the suppression of the mass peaceful protests, the NSCs convicted approximately 300 people. However, the king rescinded the power of the NSCs in response to international pressure and recommendations made by the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI). In its comprehensive report, the BICI found that Bahrain’s court systems systematically violated internationally-recognized fair trial principles – not allowing defendants access to legal counsel, admitting torture-coerced testimony as legitimate. However as bad as the NSCs were in 2011, the recent re-empowerment of the NSCs is worse: the law re-empowering the courts grants them power to try civilians, and unlike in 2011, the NSCs now have no temporal restrictions, leading some to say Bahrain is currently under a de facto state of emergency. This state of emergency has been aided and supported by an expansive counterterrorism framework that criminalizes all dissent.

Husain Abdulla, ADHRB’s Executive Director opened the panel by giving some context to the panel, noting how the Government of Bahrain used its judicial system against human rights defenders and activists. This judicial system has levied harsh sentences against activists, including death sentences against 14 people in 2017 alone, denoting a dramatic spike in capital punishment sentences. Then in January 2017, on top of the death sentences, the government ended its de facto moratorium on the death penalty, executing three torture victims. In addition to the death sentences, Bahrain’s court system has increasingly utilized arbitrary citizenship revocations against activists. Also in 2017, the Bahraini government initiated its first trials against civilians in military courts since 2011, when the government established the National Safety Courts (NSCs), which were used to try peaceful protesters. During the suppression of the mass peaceful protests, the NSCs convicted approximately 300 people. However, the king rescinded the power of the NSCs in response to international pressure and recommendations made by the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry (BICI). In its comprehensive report, the BICI found that Bahrain’s court systems systematically violated internationally-recognized fair trial principles – not allowing defendants access to legal counsel, admitting torture-coerced testimony as legitimate. However as bad as the NSCs were in 2011, the recent re-empowerment of the NSCs is worse: the law re-empowering the courts grants them power to try civilians, and unlike in 2011, the NSCs now have no temporal restrictions, leading some to say Bahrain is currently under a de facto state of emergency. This state of emergency has been aided and supported by an expansive counterterrorism framework that criminalizes all dissent.

Michel Forst sent a short video message to the panel about human rights defenders in Bahrain. He commended the work of Bahrain-focused organizations in the Human Rights Council, raising the poor condition of human rights defenders in Bahrain internationally with states. Forst noted that we are currently seeing the 20th anniversary of a landmark resolution on human rights defenders. States, he said, have an obligation to uphold this resolution and improve it. Indeed, it is time for states to follow through on their commitments and to implement this resolution. More specifically, he noted that his mandate has been very active on the case of human rights defenders in Bahrain. He concluded his remarks by calling on the Bahraini authorities to immediately release all human rights defenders currently in prison in Bahrain.

Michel Forst sent a short video message to the panel about human rights defenders in Bahrain. He commended the work of Bahrain-focused organizations in the Human Rights Council, raising the poor condition of human rights defenders in Bahrain internationally with states. Forst noted that we are currently seeing the 20th anniversary of a landmark resolution on human rights defenders. States, he said, have an obligation to uphold this resolution and improve it. Indeed, it is time for states to follow through on their commitments and to implement this resolution. More specifically, he noted that his mandate has been very active on the case of human rights defenders in Bahrain. He concluded his remarks by calling on the Bahraini authorities to immediately release all human rights defenders currently in prison in Bahrain.

Khalid Ibrahim, the Director of the Gulf Center for Human Rights, began his remarks by noting that in Bahrain, the government systematically uses its judicial system to target activists and human rights defenders. Under a judiciary that is close to the government, judges imprison dissidents and activists to lengthy jail terms on spurious charges, including bogus counterterror charges and even sentence dissidents to execution for participating in peaceful protests or calling for reforms in the country.

One of the most important ways the government uses the court system to further its repressive mechanisms is by effectively granting impunity to security officials for extrajudicial killings and torture. By granting security officials impunity, Bahrain’s criminal system consistently fails to protect and deliver justice for activists and human rights defenders from an excessively-empowered security apparatus. In this way court system underpins systematic human rights violations. Perhaps this stance is unsurprising given that the king chairs the Supreme Judicial Council and thus oversees Bahrain’s judiciary.

Ibrahim noted several cases of human rights defenders who have been sentenced to prison terms for their activism after unfair trials. He raised Abdulhadi al-Khawaja who is serving a life sentence for his peaceful activities after he was disappeared, sexually assaulted, and tortured. He also raised Nabeel Rajab’s case. Rajab, a founder of the Gulf Center for Human Rights and the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, was sentenced to prison for talking to media about human rights and issues related to torture.

But women human rights defenders are not spared torture and abuse in prison. The fact that torture, impunity, and unfair trials take place across the board demonstrates the failure of authorities to protect all citizens, and the systematization of judicial repression. Ibrahim concluded by calling on Bahrain to release all human rights defenders and citizens who are in prison simply for exercising their rights to freedom of assembly, expression, opinion, and thought and to ensure thorough and impartial investigations, and further to investigate unlawful killings and prosecute those responsible. Ultimately, Bahrain must meet its international obligations.

Hanan Salah, Libya and Bahrain researcher at  Human Rights Watch, focused her remarks on the systemic problems facing Bahrain’s judiciary. One problem is that the government is cracking down on human rights defenders, activists, and journalists with little concern for international criticism. What is contributing to this problem is that there appears to be no international cost to Bahrain’s efforts to roll back freedoms since the acceptance of the BICI. We need to ask ourselves, whether, despite the BICI’s good recommendations, if the government has a carte blanche for repression? More specifically, are we at a stage where we can say there is no cost for Bahrain to continue its repression?

Human Rights Watch, focused her remarks on the systemic problems facing Bahrain’s judiciary. One problem is that the government is cracking down on human rights defenders, activists, and journalists with little concern for international criticism. What is contributing to this problem is that there appears to be no international cost to Bahrain’s efforts to roll back freedoms since the acceptance of the BICI. We need to ask ourselves, whether, despite the BICI’s good recommendations, if the government has a carte blanche for repression? More specifically, are we at a stage where we can say there is no cost for Bahrain to continue its repression?

The repression of dissent is so widespread and pervasive largely because Bahrain’s ruling family has taken a “with us or against us” posture. Where the courts are meant to be a neutral arbiter and to dispense justice impartially, they have rather become a political tool at the hands of the government, which has used the courts to impunity in the judicial system. As a political tool, the courts have become a venue for systematic abuses and fair trial violations. Indeed, HRW has observed increasing fair trial abuses since March 2012, including incommunicado detention, and systematic and serious allegations of torture, including sexual assault against men and women. HRW has concluded that these abuses do not reflect the practices of individuals, but rather a systematic issue of state repressions.

2017 was a dangerous year: it saw the re-empowerment of the National Security Agency to security powers, as well as legislation authorizing the trial of civilians in military courts. Moreover, human rights oversight bodies meant to restrict abuses have been increasingly exposed as paper tigers, incapable of serious action, helping to ensure that impunity is rampant. In addition, there has been an acceleration of reprisals against human rights defenders and their relatives in order to silence them, including travel bans, intimidation, and harassment.

Because of health reasons, Maytham al-Salman was unable to participate in the panel. Manon Karatas of FIDH read a statement prepared by Sheikh Maytham. In his statement, Sheikh Maytham highlighted Bahrain’s use of its judiciary to target human rights defenders activists, saying that Bahrain fails to respect its international obligations concerning fair trails. That courts have imprisoned hundreds for dissent highlights the extent to which the government will go to silence criticism. These sentences contravene the BICI’s recommendations that all persons jailed for exercising their fundamental freedoms have their sentences reviewed and dropped. The empowerment of military courts to try civilians and recent convictions in the courts against civilians direct attacks on the BICI’s recommendation, and the levying of death sentences in these courts clearly violate international human rights obligations and principles.

Because of health reasons, Maytham al-Salman was unable to participate in the panel. Manon Karatas of FIDH read a statement prepared by Sheikh Maytham. In his statement, Sheikh Maytham highlighted Bahrain’s use of its judiciary to target human rights defenders activists, saying that Bahrain fails to respect its international obligations concerning fair trails. That courts have imprisoned hundreds for dissent highlights the extent to which the government will go to silence criticism. These sentences contravene the BICI’s recommendations that all persons jailed for exercising their fundamental freedoms have their sentences reviewed and dropped. The empowerment of military courts to try civilians and recent convictions in the courts against civilians direct attacks on the BICI’s recommendation, and the levying of death sentences in these courts clearly violate international human rights obligations and principles.

Antoine Madelin, Director of international  advocacy at FIDH, used his remarks to indicate how the targeting of Nabeel Rajab for his free expression demonstrating Bahrain’s sophisticated form of judicial repression. He backed up momentarily to discuss the 2011 protests, which helped spur international pressure and the creation of the BICI and its concrete policy recommendations. Bahraini authorities initially tried to show they were respecting these recommendations. But as international pressure lessened authorities began to attack members of civil society.

advocacy at FIDH, used his remarks to indicate how the targeting of Nabeel Rajab for his free expression demonstrating Bahrain’s sophisticated form of judicial repression. He backed up momentarily to discuss the 2011 protests, which helped spur international pressure and the creation of the BICI and its concrete policy recommendations. Bahraini authorities initially tried to show they were respecting these recommendations. But as international pressure lessened authorities began to attack members of civil society.

For example, throughout his trials for free expression-related crimes concerning criticizing the war in Yemen and torture in Jau Prison, Nabeel has undergone dozens of hearings. His first trial for giving televised interviews had 15 hearings, while his trial for tweets had 20 different hearings, with authorities sometimes announcing the hearings only a few days before holding them. He is not the only activist to face express-related crimes. For example, Abdulhadi al-Khawaja has a life sentence for his role in the protests, Nedal al-Salman is banned from travelling, Ebtisam al-Saegh, was reprised against for her human rights work, and Naji Fateel, the head of the Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights was given 15 years in prison.

Justin Shilad, MENA research associate with the Committee to Protect  Journalists, set out to give an overview of how Bahrain’s judiciary has targeted journalists. For example, he noted that al-Wasat journalist Mahmoud Aljazeeri had his 15 year sentence upheld and his citizenship stripped. Al-Wasat itself was forced out of its offices after the government had ordered it to cease publication. Yet, the international community has said nothing.

Journalists, set out to give an overview of how Bahrain’s judiciary has targeted journalists. For example, he noted that al-Wasat journalist Mahmoud Aljazeeri had his 15 year sentence upheld and his citizenship stripped. Al-Wasat itself was forced out of its offices after the government had ordered it to cease publication. Yet, the international community has said nothing.

But these attacks on journalists have been around since 2011 when two reporters for al-Wasat including Karim al-Fakhrawi were killed in security force custody. Security forces also shot and killed journalist Ahmed Hasan as he covered a peaceful protest. Yet despite the judiciary’s success in prosecuting dissidents, it has refused to prosecute instances of impunity. Increasingly, the government has been utilizing counterterror rhetoric against journalists. For example, Ahmed Humaidan was sentenced to 10 years in prison as he covered an attack on a police station because “he participated in the attack.” He has also been denied family visits and although he has a severe eye infection and he needs necessary treatment to save his vision, authorities are not allowing him to receive help. Outside actors have, at times, exacerbated the rights crisis, as US President Donald Trump visited Bahrain and stated there would be no more strain in the bilateral relationship. Bahrain has responded with a systematic campaign against journalists, particularly during its UPR review, when it did not allow any journalists to travel. More recently, the government has used the conflict against Qatar as a reason to crack down on journalists.