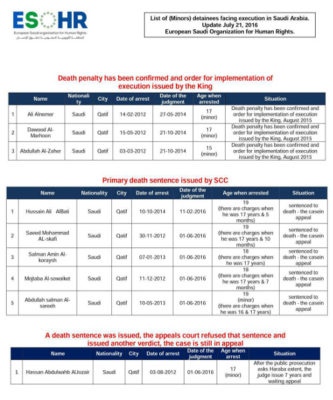

Since 2011, Saudi authorities have arrested more than 60 children, among them Ali al-Nimr, Abdullah al-Zaher, Dawood al-Marhoon, Ali al-Rabeh, and Amin Mohammed Aqla al-Ghamidi. It has executed some of them, including al-Rabeh and al-Ghamidi. Others, like al-Nimr, al-Zaher, and al-Marhoon, remain in custody awaiting execution or the death penalty. At least 10 young men are currently in Saudi prisons, facing death sentences for crimes the government says they committed while they were juveniles.

Ali al-Nimr, Abdullah al-Zaher, and Dawood al-Marhoon are well-known victims of Saudi Arabia’s flawed justice system that allows the government to prosecute minors and young people for crimes committed as minors. Security forces arrested them in 2012 when they were teenagers, tortured them into confessing, and sentenced them to death under the anti-terror law for their participation in peaceful protests. They have since exhausted all legal appeals and authorities could execute them at any time.

Abdulkareem al-Hawaj is another young man who faces execution in Saudi Arabia. Born in November 1995, he was arrested in January 2014 while he was walking home from work and subsequently forcibly disappeared. The men who arrested him wore civilian clothing and were possibly linked to the General Directorate of Investigation, which supervises the domestic intelligence service—the mabahith. Officials disappeared him for five months, during which time he was placed in solitary confinement. Authorities also tortured him into confessing to crimes officials accused him of committing. Authorities did not allow him to contact a lawyer for two years. Even after Abdulkareem received a lawyer, officials harassed the lawyer, and the court did not respond to his lawyer’s requests for information. On 27 July 2016, Saudi Arabia’s anti-terror Specialized Criminal Court (SCC) issues its initial judgement against Abdulkareem. It sentenced him to death on accusations related to charges dating to when he was 16-years old.

Additionally, the European-Saudi Organisation for Human Rights (ESOHR) has documented six other young men who face the death sentence. The Saudi government arrested and charged many of them in the SCC for crimes they allegedly committed as minors. Some of them have faced torture, and ESOHR has documented instances where interrogators wrote confessions and tortured the victims into signing them. The SCC’s initial ruling in Hussein Ali al-Bata’s case resulted in a death sentence. As of 4 March 2016, Saeed Mohammed al-Skafi, Salman al-Quraysh, Mojtaba al-Suwaiket, Abdullah al-Surih, and Hassan al-Jazer were in the middle of trials at the SCC, where the public prosecutor called for them to be sentenced to death.

Aside from the fact that the public prosecution has demanded the death sentence for alleged crimes committed as minors, little more is known about many of Saudi Arabia’s alleged juvenile offenders. Information about prisoners and judicial proceedings is hard to come by, as the kingdom’s justice system is arbitrary and secretive, with the media offering only sparse or fragmented details. In addition, many protesters, including children, have remained in jail or been tried in secret.

Saudi Arabia acceded to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in 1996 and to the Convention Against Torture in 1997. However, it has continued to torture detainees and sentence people to death for alleged crimes committed as children. Saudi Arabia needs to reform its legislation to ensure it complies with its international human rights obligations. It needs to promote judicial transparency, particularly concerning cases of juveniles and young people. Ultimately, the kingdom needs to ensure that children are neither considered nor treated as criminals necessitating execution.