Since Bahrain’s pro-democracy uprising began in 2011, Americans for Democracy & Human Rights in Bahrain (ADHRB), the Bahrain Institute for Rights and Democracy (BIRD), and the Bahrain Centre for Human Rights (BCHR) have documented numerous cases of government retaliation against human rights defenders and activists. Less well-known, however, are cases of retaliation against these individuals’ families and friends – those targeted simply for knowing or being related to an activist or a victim. This retaliation can take many forms, from arbitrary detention and torture to recurrent harassment. For the relatives of those killed by the authorities, the experience is one of injustice compounding injustice – an additional act of intimidation meant to discourage them from seeking accountability for the death of a loved one. January’s Champions for Justice highlights victims of government reprisal who were targeted because of their association with victims and activists.

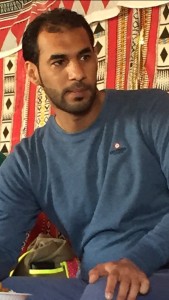

Ali Isa Ali al-Tajer is a manager at the Al Khunaizi Group construction company and the brother of Mohamed al-Tajer, a prominent human rights defender and lawyer who has worked with the United Nations Secretariat on the situation in Bahrain.

Ali Isa Ali al-Tajer is a manager at the Al Khunaizi Group construction company and the brother of Mohamed al-Tajer, a prominent human rights defender and lawyer who has worked with the United Nations Secretariat on the situation in Bahrain.

On 5 November 2015, Bahraini security forces surrounded Ali’s home with more than nine vehicles. Ten masked men forcibly entered the house and arrested Ali. They failed to present a warrant or provide any reason for the raid and arrest. With the exception of two brief phone calls, officials held Ali incommunicado for 25 days.

On 30 November, without prior warning, the public prosecution called Mohamed al-Tajer to represent his brother in court. By the time Mohamed arrived, the hearing had already begun, and Ali had not had access to any counsel. The public prosecutor claimed that Ali confessed to joining an illegal terrorist organization for the purposes of overthrowing the government. Ali maintained his innocence, telling the court that the authorities had tortured him into providing a false confession. Moreover, he stated that he had been blindfolded when he was forced to sign the document; he never knew what he was signing. The prosecutor told Ali to stop explaining his torture, stating that he would refer the allegations to the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), a branch of the public prosecution purportedly dedicated to pursuing cases of government abuse.

After the proceedings concluded, Ali told Mohamed that security officials severely tortured him while he was in detention, subjecting him to humiliation, physical beatings, and sexual assault. He also revealed that the prosecutor had threatened him prior to Mohamed’s arrival at court.

As of 4 January 2016, Mohamed was able to see his brother twice more since the original hearing. Ali has developed several long-term injuries as a result of the torture he has suffered while in detention, including a bulged disc, a hernia, and the loss of hearing in his left ear. Authorities took Ali to a forensic medical examiner, who reportedly recommended Ali see an orthopedist and urologist. Although the forensic examiner has not released a report on Ali’s examination, the Public Prosecutor stated to the court that the forensic examiner found no evidence of torture.

After one of his visits with Ali, Mohamed informed the SIU that clothes he took from his brother at the Criminal Investigative Directorate (CID) had bloodstains on them. The SIU summoned Mohamed for questioning, which he reported was routine in nature. The authorities continue to postpone Ali’s appointments with the medical specialists, and he has since missed three appointments. This delaying tactic has been previously documented by ADHRB, BIRD, and BCHR, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch as a way for the SIU to report that an investigation has been opened to satisfy the courts.

Mohamed describes Ali as an apolitical person and suspects that the government is prosecuting him in retaliation against Mohamed’s own human rights work. Though Ali’s family has filed a complaints on his case with the Bahrain National Institute for Human Rights (NIHR), the Ministry of Interior’s Office of the Ombudsman, and the SIU, they worry that the complaint process will be a futile exercise at best. At worst, they fear that the authorities may exploit the mechanism’s lack of independence as a means for further reprisal. ADHRB, BIRD, and BCHR have found that several victims have been targeted for additional torture in retaliation for filing complaints with the Ombudsman, for example. If the government is actively targeting Ali as a reprisal against Mohamed, he and his family may be at risk of further abuse simply for submitting a complaint.

Abdulhadi Mushaima is the father of Ali Mushaima, a 21-year-old Bahraini citizen who was shot and killed by security forces on 14 February 2011. Ali was the first demonstrator to be killed during the pro-democracy protests that began in 2011.

Abdulhadi Mushaima is the father of Ali Mushaima, a 21-year-old Bahraini citizen who was shot and killed by security forces on 14 February 2011. Ali was the first demonstrator to be killed during the pro-democracy protests that began in 2011.

Since the death of his son, Abdulhadi has faced repeated harassment by the authorities. On 22 August 2013, security forces raided his home without warrant or permission. They arrested Abdulhadi without providing any reasons and held him in custody for a week before his eventual release on 29 August.

Almost a year later, on 9 May 2014, Abdulhadi received a summons to appear at the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) on 12 May. When Abdulhadi arrived, the authorities ordered him to refrain from participating in any demonstrations, specifically those calling for government accountability for Ali’s death. The officials demanded that Abdulhadi sign a pledge stating that he would never take part in any marches or demonstrations again.

Makky Abu Taki is the manager of a real estate company and the father of Mahmoud Abu Taki, a 22-year-old student who was shot and killed by Bahraini authorities on 17 February 2011 when security forces stormed the Pearl Roundabout.

Makky Abu Taki is the manager of a real estate company and the father of Mahmoud Abu Taki, a 22-year-old student who was shot and killed by Bahraini authorities on 17 February 2011 when security forces stormed the Pearl Roundabout.

Like Abdulhadi Mushaima, Makky experienced persistent government harassment after the loss of his son. On 26 November 2013, security officials summoned Makky to the Al-Naim police station and arrested him. The next day, authorities took him to the Public Prosecutor’s office for interrogation. When the prosecutor finished with his questions, he charged Makky with unlawful assembly and inciting hatred against the government, ordering his detention at Dry Dock (Al-Howdh Al-Jaaf) Prison pending further investigation.

While in custody, security officials severely mistreated Makky. In a phone call to his family, Makky said that prison guards regularly beat and humiliated him. Makky’s family reports that the Dry Dock administration infringed on their visitation rights, consistently preventing them from seeing Makky without providing any justification. The government held Makky for nearly a year, until 9 January 2014, when he was released.

While in custody, security officials severely mistreated Makky. In a phone call to his family, Makky said that prison guards regularly beat and humiliated him. Makky’s family reports that the Dry Dock administration infringed on their visitation rights, consistently preventing them from seeing Makky without providing any justification. The government held Makky for nearly a year, until 9 January 2014, when he was released.

Four months after his release, Makky received the same summons as Abdulhadi Mushaima, requiring him to appear at the CID office on 12 May. There, he faced the same harassment: the authorities told him that he could no longer participate in any marches or protests – particularly those related to his son’s killing or the current political situation – and forced him to sign a corresponding pledge.

Click here for a PDF of this post.